Archived Insight | October 11, 2017

Should The Fed Ease Its Rate Hike Plans to Support Productivity Growth?

By John Ross

The relatively modest productivity gains made during the current U.S. economic recovery is part of why jobs have not come back as strong as in the past. It also might make the Federal Reserve (Fed) rethink its plan for raising interest rates in the future.

Productivity growth is cyclical – its strength or weakness depends heavily on how the economy is doing. Traditionally when unemployment is high, companies can increase hiring more easily because there are plenty of available workers. This is what later leads to faster productivity growth and therefore economic growth.

Also traditionally, when the U.S. economy is doing better, it is harder for companies to hire because most employable people have jobs. Therefore, to continue to grow productivity, firms must increase wages in order to grab workers from other firms. This usually leads to higher inflation, which helps companies boost prices and pay workers more. In recent recoveries, this has been less of the case.

Why Has Productivity Grown in Recent Recessions and Weakened in Boom Times?

While companies are reluctant to cut workers’ wages in recessions because of low inflation, they are hindered from raising prices. Also, firms have implemented job related cost saving measures such as outsourcing and automation, and have cut more routine jobs. In recessions, because of these measures and because of a more flexible U.S. work force, companies know they can lay off workers and then re-hire when times are better.

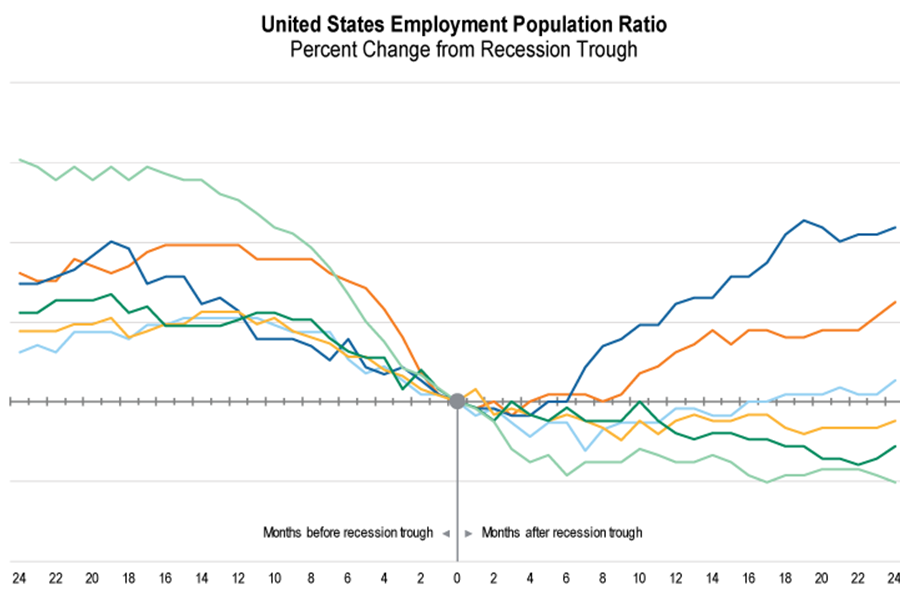

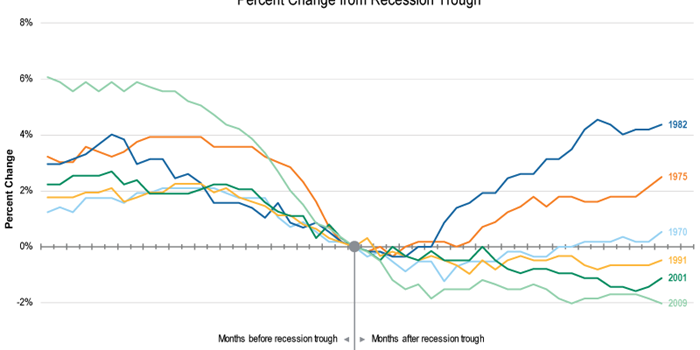

While companies can view this as an exchange for the prospect of maintaining or expanding profit margins, it’s often less supportive of economic growth. We have also seen so-called “jobless recoveries” since the 1980s (see chart). This is generally for the same reason – the cost cutting measures that helped companies in down economic times have helped firms meet rising demand in improving economies without having to hire new workers. Until a rising inflation environment supports price increases and additional hires, unemployment and overall economic growth may remain muted.

Is the Fed Underestimating the Problem of Low Inflation?

Some say that the Fed might be underestimating the problem of low inflation in this more recent era and that an easier monetary policy might be in order so that productivity has its best shot at continuing to grow, and the most workers have the best shot at finding employment. They point to March 1997, when the U.S. economy seemed to be growing robustly and unemployment was relatively low.

The Fed planned to begin a rate hiking cycle then, but changed its mind when Fed members took into account how new technologies and cost cutting measures changed demand for labor in recent years. The Fed stopped hiking rates, and the late 1990s was one of the U.S.’s strongest periods of labor productivity, with unemployment declining even further over time.

It’s not clear whether the current era is like the late 1990s, and if there is much more productivity growth to come (or if the unemployment rate will continue to fall). However, some Fed watchers think that the central bank should keep its policy relatively easy for the near future, given the possibility for further productivity and job gains in a still low inflationary environment.

Given productivity’s importance as an indicator of economic growth, Segal Marco Advisors will be examining trends in productivity as we develop our Q3 2017 Investment Outlook – coming soon.

Given productivity’s importance as an indicator of economic growth, Segal Marco Advisors will be examining trends in productivity as we develop our Q3 2017 Investment Outlook – coming soon.

For more insight on this topic, read The Economist’s piece, "Pessimism about productivity growth may prove self-fulfilling."

The information and opinions herein provided by third parties have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. This article and the data and analysis herein is intended for general education only and not as investment advice. It is not intended for use as a basis for investment decisions, nor should it be construed as advice designed to meet the needs of any particular investor. On all matters involving legal interpretations and regulatory issues, investors should consult legal counsel.