Articles | November 19, 2021

The Science of Benchmarking: It’s Complicated, but Important

We recently noticed some comments on the topic of benchmarking that seemed to malign the work of asset owners and their consultants in developing methods for judging the success of an investment program. While there is little doubt that some folks have long used somewhat questionable approaches to this process, in the hope that they could somehow convince an audience that misfires were successes, by and large developing benchmarks is grounded in sound logic, consistent reporting and clarity.

This article will outline that process with at least one clear conclusion: An allocation of 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds has no place in a discussion on the topic and fails as a standard by every measure.

The benchmark hierarchy

There are four key levels that constitute the benchmark hierarchy shown in descending order of importance.

Step 1: What is the purpose of the asset pool?

Each investment program exists for a specific purpose, whether it be to pay retirement benefits, provide financial support for a university or simply be held in preparation for the proverbial “rainy day.” Derived from this rationale, there should be associated levels of return and risk necessary to achieve the overarching objective of the pool. Clearly, these should be consistent with reasonable expectations for capital markets in terms of forward-looking returns, volatility and correlations, but they must also describe the horizon required to achieve the stated goals. This step in benchmarking hierarchy often gets insufficient attention relative to how critical it is for success. It provides the stable roadmap for all other aspects of investing. As Yogi Berra once said, “If you don’t know where you’re going, you might wind up somewhere else.”

We also recommend that this goal and progress towards its achievement should be contained in every investment report. It should be reassessed periodically, particularly based upon organizational and fund dynamics. Importantly, while this is ultimately the province of the asset owner (board, committee or other), it is of great value to include other parties who may be stakeholders or professional service providers, including actuaries and asset consultants.

These parties can apply sophisticated forward-looking methodologies to develop a baseline allocation of assets to the various asset classes with the goal of developing the optimal combination with the highest likelihood of achieving the stated goals. An often-overlooked step in this process is to stress test the results of these simulations for sensitivity to different market environments and within the context of the interrelationship between changes in markets and changes in the dynamics of the ultimate objective of the asset pool. These include cash-flow analysis, asset/liability modeling and downside assessment.

Step 2: The passive (or nearly so) implementation of a dynamic asset allocation

Once a clear investment objective for the asset pool with an appropriate time frame has been established, an investible portfolio must be constructed that can meet that objective. The portfolio’s goal is to meet or exceed the return objective over the time period at an acceptable or fairly compensated level of risk as defined by volatility. The goal should not be to maximize the return only, but rather to target the amount of risk in the portfolio while still meeting the portfolio objective. (In other words, to maximize risk-adjusted performance as measured by the Sharpe Ratio: excess returns over the risk-free rate, divided by the standard deviation of the portfolio.) For example, if the goal is to return 1.3 percent from today to September 20, 2031, a plan could purchase a 10-year U.S. Treasury that is currently yielding exactly that amount and then pursue other activities as the investment objective is virtually locked in.

To create the right asset allocation, a plan must first choose the appropriate asset classes for achieving that goal and then make calculated assumptions about the future returns, risk and correlation of those asset classes. From these assumptions, a portfolio optimizer can be used to generate multiple combinations of these asset classes and create an efficient frontier showing the highest portfolio returns that can be generated at various levels of risk. From that exercise, a target portfolio can be selected that generates the desired returns over the projected time period, understanding that it is the best estimate at the least risky portfolio for that return objective.

When choosing asset classes, they should be investible to create a true benchmark. However, in a number of cases this is not possible. Examples of this include fixed income indices that incorporate bonds that simply do not trade or are not liquid enough to be held in a portfolio or other private market asset classes that, by definition, not everyone is readily able to access and invest. Therefore, a best representation of the selected asset classes are used in the benchmarking process, rather than an investible universe.

However, much as markets are dynamic, so should be both the assumptions on the asset classes and, therefore, the optimal portfolio. While an asset allocation is a static long-term portfolio objective, it needs to adapt to a changing investable universe. The assumptions need to be revisited on a regular basis to make sure they still align with the long-term possibilities of the markets being used. This includes not only return assumptions, but risk and correlation as well.

The portfolio should be periodically reassessed, and a new portfolio asset allocation should be established or the existing asset-allocation target should be confirmed. We refer to “target” because there are times when the actual portfolio asset-class weightings will deviate from the originally established portfolio, due to dispersed asset-class returns and changing valuations. When these deviations are so large as to change the potential risk and return relationship of the portfolio, it should be rebalanced back to the original target. The guidelines for this rebalancing should be established when the risk/return objectives are established to ensure that the portfolio remains within guidelines that are comfortable for the plan to continue to meet its return objectives at acceptable risk levels and to provide a systematic guideline and course of action in a period when markets may be highly volatile. The rebalancing methodology should be systematic and clearly laid out.

A benchmark should also not be a simple use of market dictation. A plan should not just “buy the market” because the market’s configuration most likely does not match the long-term goal of the plan. For example, if a plan were to buy the market based on market-capitalization-based weightings, that plan would end up with a bond-heavy portfolio of approximately 52 percent bonds, 41 percent stocks, 5 percent real estate and 2 percent private equity. This may or may not meet the long-term objectives of the portfolio and additionally appears to be a naive way of allocating capital.

In addition, the asset allocation should not be static for the entire period of investment. A dynamic market requires equally dynamic adjustments to the portfolio allocation. Simply choosing a portfolio that is 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds because it has done well historically increases the certainty of having a portfolio that is too volatile for stated return objectives in some periods and takes on too little risk to generate the level of returns required in others.

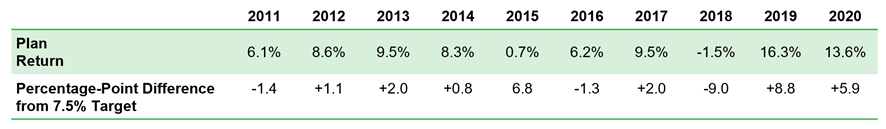

For example, if a plan were to have arrived on January 1, 2011 with perfect foresight as to the returns for U.S. bonds (Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index), U.S. stocks (Russell 3000) and non-U.S. stocks (MSCI ACWI ex-U.S.) as well as the standard deviation and correlation of those returns over the next 10 years, they would have had a clear advantage on forecasting the optimal portfolio to meet their return objectives. With this perfect foresight, a plan with a 7.5 percent return objective would have constructed an allocation of 35 percent Russell 3000, 65 percent of Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index and 0 percent to the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. (knowing that non-U.S. stocks were about to return 5.5 percent with a 17 percent standard deviation over the next 10 years). The plan trustees would have looked at that the portfolio 10 years later on December 31, 2020 and seen that their plan had generated a 7.9 percent annualized return with a 5.5 percent standard deviation and everyone would have been happy. Or would they? The 65 percent bond/35 percent stock portfolio would have generated the annual returns shown in following chart (assuming an annual rebalance).

The first year may have generated some difficult discussions and decisions in meeting planned distributions or payments due from the plan. While the next three years would have been cause for celebration, the years 2015, 2016 and 2018 would also have been difficult for the plan sponsor to talk about their “perfect” plan allocation. While in the years 2015 and 2018 it would have been impossible for anyone to generate a 7.5 percent return using this simple portfolio of three asset classes, there are an equal number of years where the volatility of equities was not necessary to meet the plan objective (such as the last two years, 2019 and 2020 when bonds returned 8.7 percent and 7.5 percent, respectively).

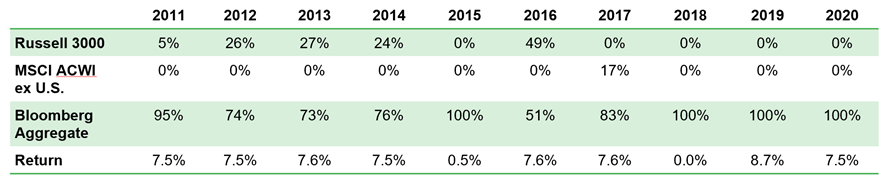

The following chart shows the optimal asset allocations to achieve 7.5 percent returns (or to best protect capital when a 7.5 percent return was not possible) with perfect foresight as to the returns over the next 12 months:

So, in most cases, despite the positive outcome of generating a 10.1 percent return over the 10 years ending December 31, 2020, a 60 percent equity and 40 percent bond portfolio would have been taking on too much risk to meet the plan’s return objective.

Step 3: Don’t live in a vacuum

The next level of benchmarking provides a bit of a gut check as to the appropriateness of the conclusions reached in the first tiers by comparing your results to peers. The first two steps are developed internally without real consideration of how other asset owners have approached their own development of goals and asset allocation. By comparing results to peers, one can gain some understanding of whether you are substantially different and if so, it warrants an exploration of why. Further, this assessment helps shed light on or measure the relative opportunity cost or benefit experienced by a plan associated with its specific manager or strategy selection process. Comparisons should be relative to asset pools with similar characteristics such as purpose or type (e.g., public vs. corporate) and size, to provide the most relevant results. For example, to compare results of a $10 billion governmental DB plan to a $50 million multiemployer strike fund would provide little value. There are numerous peer benchmarks available for asset owners allowing for valid and robust analysis with large (preferred) numbers of participants.

The results of these comparisons are less important to achieving success than the first two tiers; and may simply not be of any significance if the asset pool has unique characteristics that create a wide divergence in asset allocation. A case in point might be a new corporate DB plan (noting that this doesn’t seem to be happening these days) where its peers are likely to be in the cash-flow negative or asset/liability matching stage.

Step 4: Manager-specific goals

Once an investable asset allocation has been determined that will best meet the return objectives of the plan, investment strategies must be chosen to execute those allocations. Each strategy that is selected must be measured against an appropriate benchmark to best determine how well it fulfills its role in the portfolio. These benchmarks should be used to both measure the ex-post success in relative performance terms but also to determine that the strategy is remaining consistent with the asset allocation segment’s return profile for both risk and return. Underperformance and outperformance both can be a red flag for style drift and must be monitored. Therefore, to best measure performance, a chosen benchmark must be consistent with both the segment of the portfolio the strategy is used to represent and the strategy’s specific style.

Typically, the strategy benchmarks chosen do not all roll up neatly to the overall portfolio benchmark. This is because strategies may represent a sub-segment of the portfolio that do not have a benchmark represented by a sub-segment of the portfolio index. For example, a non-U.S. strategy that does not incorporate emerging market stocks could be benchmarked to the MSCI EAFE index and not the overall plan’s benchmark, the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. (which does contain emerging markets). If a separate manager is hired to manage a dedicated emerging markets portfolio, the combination of the MSCI EAFE and the MSCI Emerging Markets may not roll up to the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. benchmark used by the overall portfolio. But the two underlying benchmarks are a close approximation of the overall benchmark, as the MSCI EAFE plus the MSCI EM index has a correlation of 0.99 to the MSCI ACWI ex-U.S. over the past 10 years. More importantly, it is a better way to measure and evaluate the performance of the two underlying strategies and therefore a better way to benchmark performance.

Other examples of where underlying benchmarks deviate from the plan benchmarks but are wholly necessary include private markets, such as real estate, private equity or private credit. In each of those markets, there is no perfect benchmark that measures the performance of all possible private investments. There are approximations, such as the broad based NCREIF ODCE Index for open-end core real estate or the Cambridge Thomson Index for private equity, that measure the performance of underlying managers. However, those may not be ideal measures for strategy performance, especially as they are not investible per se and rely on voluntary peer reporting, which may contain other flaws, such as survivorship bias. In addition, given the diversified investment opportunity set, many managers focus on specific niches of private markets and these strategies are not necessarily homogeneously captured in an asset class performance composite.

What’s Survivorship Bias?

In benchmark construction, survivorship bias is the tendency to view the performance of stocks or funds in the market as a completely representative sample without including those that folded or failed in some way, because that “failed” group is no longer in the data set.

The same is true of levered or hedge strategies, which use various investment instruments and strategies to create a portfolio with a unique return set. These strategies are not fully captured in a broad hedge fund or absolute-return strategy benchmark that can be used for an overall portfolio. Therefore, it is often best to focus on individual strategy benchmarks to measure their performance and a broad-based benchmark at the portfolio level to represent that asset class and measure the success in picking the underlying strategies.

Overall, it is necessary to use a different benchmark to measure underlying performance while still getting to a close approximation of the overall goal.

Yes, it’s complicated

There is a lot going on in the process of monitoring the success of an investment program, but isn’t it pretty important to be able to judge progress toward long-term goals as a method to increase the likelihood of success? Each step in the hierarchy of benchmarking plays a significant role in the process and, collectively, the information provided serves the investor well in determining whether a painstakingly developed program is on path.

It’s common for armchair quarterbacks to use hindsight to justify criticism of results simply based upon the impossible-to-predict results of capital markets over some finite time period. Long-term investors focus their attention on the primary objectives of the asset pools and then build structures deemed most likely to achieve them.

While mid-course corrections and continuous oversight are important, it is equally crucial that investors not be deterred by looking in the rearview mirror and concluding that the most recent past is repeatable. Yogi Berra’s aforementioned accurate portrayal of goal setting notwithstanding, it behooves the investor to spend the time and effort to build guideposts along the way to make sure the trip is as smooth as possible.

See Related Insights

The information and opinions herein provided by third parties have been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. This article and the data and analysis herein is intended for general education only and not as investment advice. It is not intended for use as a basis for investment decisions, nor should it be construed as advice designed to meet the needs of any particular investor. On all matters involving legal interpretations and regulatory issues, investors should consult legal counsel.